JOURNAL

documenting

&

discovering joyful things

The memory-map

The first thing I painted was the 14th-Century chateau, one night after we had explored it with our friend Tonia. We’d set out early that morning with a backpack stuffed with chopped vegetables, bananas, baguettes and the homemade koulourakia we’d baked the day before from a Meals in the Mail recipe, to walk the ramparts all the way around town.

At the chateau we stopped to catch our breath and polish off our little lunch, sitting on the ancient stone wall amid glorious pink and red flowers, before buying four tickets at the gate and heading inside to explore. The chateau is formally known as “donjon de la duchesse Anne,” or “the keep of Duchess Anne,” a woman beloved as a ruler and protector of Brittany from 1488 until her death, as well as being Queen Consort of France (twice).

Today, her keep is almost empty: no roped-off antiques or baltic pine replicas here, just empty rooms with carved shutters half-closed over diamond-paned windows. It made space for the ghosts, and we could almost feel the past walking among us in those empty rooms. We climbed the narrow spiral-stone staircase up, up, wandering the rooms where once the Duchess Anne ate, conversed and slept, until we emerged to blinding sun and gusting winds on the roof. Then we headed down. Down, down, into the smoke-stained ‘dungeon’ of a kitchen, where there were no windows and Tonia and I had to use our iPhones as torches so that we could all make it down the final flight of stairs without breaking any limbs.

At various levels (especially in the guards’ rooms), medieval toilets were cut into the stone and, from the smell, were still occasionally in use. We only just - with seconds to spare - managed to stop four-year-old Ralph from doing the same, and the laughter from our little party at this lucky escape carried us all the way back to our still-new (to us) apartment.

So later that night, when the children were sleeping the deserved sleep of the utterly exhausted and Tonia and I sat up eating cheese and drinking rosé, I drew the chateau on the blank paper of my future map, and wrote our little story down next to it.

Piece by piece, as we built memories, I added them to the map. Picnics at the nearby ruins. Baguettes from our favourite boulangerie. Trips to Saint Malo, le Mont Saint Michel, and Broceliande. The carousel the children loved to ride, where first Scout announced, “Our town is amazing!” The church with the bells that punctuated our days and nights with such beauty. The big, old English sheepdog we called Sarah, from that time I said “Look, that dog has it’s hair up” and Ralph replied, “How do you know it’s called Sarah?”

Painting at night after each adventure, there wasn’t any strategy or forethought to the map, and this made for lots of mistakes. I painted the Thursday markets one evening after carrying home the week’s bounty, and, a few days later, drew in the clock tower behind it after we had climbed to the top. Then a month or two further along, when I decided I needed to paint in the grand old buildings that lined the market square, the clock tower was already in the way. In my painting it has grown legs and journeyed a full block away from the rue de l’horloge, where it stood since 1498. I drew Sarah the dog before adding in the buildings around her, and it turned out she was not even remotely to scale. I had accidentally turned her into a canine giant, eclipsed only by the baguettes, which are the size of some houses. Saint Malo was on a wonky slope, the abbey at Lehon slid over onto the very bottom of the paper, and a strange, ibex-like creature on the carousel loomed over everything else.

The mistakes have come to be my favourite parts of this map. I could have waited, of course, collecting these moments in my mind to faithfully reproduce them back home. Carefully copying or tracing a roadmap of Dinan, and then plotting out our favourite memories with both accuracy and artistic arrangement.

In fact, that was my original intention in making the map. After taking multiple wrong turns when trying to follow the map of the ramparts given to us by the Dinan tourism office, Tonia and I joked that I’d paint a more accurate one, and give it to them when we left.

But the best adventures are unplanned and precious moments come unbidden. And if you don’t stop to notice them when they happen, those moments can journey on by, altogether unseen.

So I chose mindfulness over method, thankfulness over design, and pasted my little acts of gratitude like patchwork all over the paper, living each drawing in the moment without pausing to plan the final piece.

When we left the village in December, I didn’t know what to do with the map. The handmade paper was so thick and large it couldn’t fit into a tube, so I carried it with me from Dinan to Paris, Paris to London, London to Cumbria, Cumbria to Inverness, Inverness to Edinburgh, and Edinburgh to Melbourne, Australia. After we returned home, it lay rolled up and forgotten on the sofa-bed in our front room for a month, buried under clothes awaiting dry-cleaning, until finally in mid-February I uncovered it and found the time - and emotional fortitude - to finish what I had started on that hot summer’s day at the chateau, back in August.

So here it is, in all its wonky, unplanned, mistake-ridden, navigationally-bereft, emotionally-rich glory. The story-map of our sabbatical in France, and a pen-and-paint act of thanksgiving.

Painting hacks (and it's ok if you're not doing it right)

Recently when I wrote my frequently asked questions post, I deliberately neglected to answer one of the questions I get asked the most often… “Can you teach me how to paint?”

The truth is that I have never felt confident enough to ‘teach’ painting, because in order to teach something it helps if you actually know what you are doing yourself! I am completely self-taught when it comes to my illustrations, and by “self taught” I mean I just keep painting, experimenting and practising… I haven’t read any books or watched any YouTube videos to improve my techniques.

(Although I’m actually hoping to remedy that this year, and take some formal lessons in botanical illustration at the Botanical Gardens in Melbourne, so maybe one day in the future I’ll have something more useful to share on here.)

But in the meantime, rather than teach you how to paint in any strict, best-practise or rules-based way, I am going to share some of the tips, tricks, hacks and techniques that I have stumbled across so far on my illustration journey.

Why it’s ok to not do it right

Because I’ve never received proper training, it is highly possible that the things I share are not the best way to do things, or that I’m simply “not doing it right.” And I think it’s important that we all seek ways to feel comfortable with this, when it comes to our own creative work.

“Not doing it right” is why I’ve held back on sharing too much in terms of how-to-paint content in the past (fear that I’m not doing it right, and fear that I’d therefore be teaching you to ALSO not do it right).

But now I’m thinking differently, and I’m going to call myself out on this defeatist attitude. Really, it’s just another form of “imposter syndrome,” the feeling most of us experience sometimes (or often) - especially when it comes to creativity - that we are not good enough, even when others appreciate our creations - and that any minute, the world will see us for the failures we secretly believe we really are.

Why do our brains do this to us?? This blog is not the place to explore the depths of human psychology (although I do talk a lot about imposter syndrome and the Inner Critic in my Create with Confidence course), but today I will stand up to my own Inner Critic and hopefully bolster you to stand up to your own, by sharing my perfectly-imperfect tips for watercolour painting.

My hope? That you will a) find some tips in here that are useful, but b) even if nothing here is useful, that you will feel empowered to experiment, play and create, without the constraints of “doing it right.” Just go for it!

Ok, shall we get started?

1. It’s ok to pencil first

You know those Instagram and YouTube videos in which people deftly put wet brushes to clean, white paper and in a matter of minutes create beautiful floral wreaths or sleepy cats on cosy couches, or potted succulents in greenhouses full of charm?

Yep, I can’t do that either.

I sketch my picture out using pencil first (2B because anything darker becomes harder to rub out later), then use waterproof black pens (my preferred brand is Sakura Pigma Micron) to draw it exactly the way I want it to look. Depending on what I’m wanting for the finished product, I add in more or less pen detail, and when that’s done, I rub out the pencil marks.

By the time I come to do the painting, it’s really not much more than colouring in.

2. Painting tools (otherwise known as “You can get your paints from the supermarket”)

My father always used to tell me “It’s a poor workman who blames his tools,” and this is as true in the art-room as it is in the workshop, garden or kitchen. To whit: great tools can make life a lot easier, but they are no substitute for elbow-grease and practise.

For many years, I used sets of watercolours and gouache paints picked up in a toy-store and supermarket respectively. From time to time I still dip into my kids’ Crayola paints, and have used them for all kinds of projects, including illustrations I’ve been paid to create. Until two years ago, I was still using the used gouache paint set my grandmother gave me when I was 10 years old.

In case you’re wondering which is which:

Watercolour paints are made by mixing colour-pigment with binder. The paint is applied by wetting it and then brushing it onto paper. Once the water dries, the binder fixes the pigment to the paper. Watercolours are super-versatile because you can make the colour stronger or weaker depending on how much water you use, and you can easily blend them together or layer them over each other in-situ (i.e. on the painting itself) to create almost any colour or shade you want

Gouache paints are very similar to watercolour paints, except that an extra white pigment (like chalk) is added, to make them brighter and more opaque. (Think Toulouse-Lautrec posters and you’ll know what gouache looks like). You can also blend gouache and watercolour with one another to create just the right colour or intensity you want

Even now, my “best” paints are really hobby-grade paints (I have Winsor & Newton watercolours in a set and Reeves gouache in tubes). I’m sure an upgrade would be a good thing, but I haven’t made the plunge so far and, if you’re starting out and don’t have the means or desire to invest just yet, don’t let that stop you: some decent brushes (my favourites are 'Expression' brushes by Daller-Rowney) and a good feel for colour-blending are all you need to create lovely paintings.

Which leads me to…

3. Colour-blending 101

Alright, most of us know that there are only three primary colours (colours you can’t mix from others): red, yellow and blue. With the help of black and white, you can realistically create all the colours, shades and tones you need with just these basics.

Luckily for us, most paint sets come with a lot more options, so when we are ‘blending’, it’s to create subtlety and more realism. This is how I blend my colours:

First, I get a non-porous palette on which to mix my colours. I have an old plastic paint palette that used to belong to my grandmother, but anything non-porous will do. I also use dinner-plates, the plastic lids of my paints, anything I have handy at the time

Onto that palette, I add a small amount of the first colour, either by adding a lot of water (via my brush) to a hard colour in a paint set, or by squeezing a tiny bit of that colour from a tube

Next, I add my second colour to the palette - nearby but not touching the first - in the same way. And so on for any subsequent colours. So for example if I was making purple, I’d do this with blue and red.

Now I’ll bring a tiny bit of one colour into the middle, and a tiny bit of the other colour into the middle, and mix them together. Based on what that looks like, I’ll add little bits more of one or the other colour, until it looks right. At this point if necessary, I might bring in some other tones, for example a bit of yellow to give it warmth, or white to brighten it up, or a tiny bit of black to tone it down.

The trick is to do all of this gradually, one small bit of colour at a time, so that you can rectify any mistakes or any time you’ve overdone it with one colour, and build up slowly until you get exactly the shade you want.

If necessary, I test my blends on a scrap piece of paper, just to see how they look once they dry, and also to test how much water to add, to create the look I’m going for.

Once I’m happy, I use this new colour on my painting. If I find I’m running out, I start the process all over again but make sure to do it before the original blend has run out, so that I can match the shade as closely as possible so that my painting remains consistent.

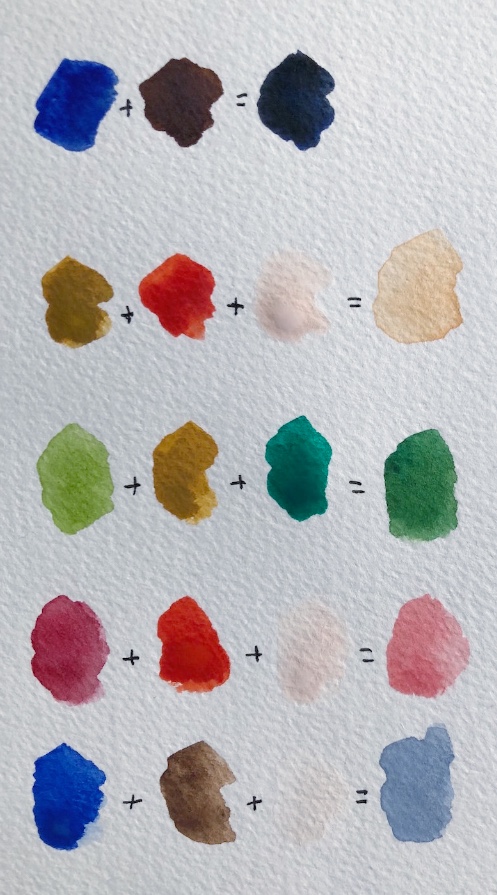

4. Colour-blending combinations that come in handy

While travelling for five months I had only the smallest of travel-paint sets, so I had to do a lot more blending to get the colours I like, than I do at home. I am drawn to a muted colour palette with soft, natural tones. But my little travel paint-kit was full of bright and primary colours. Here are some of my personal thoughts on colour, and some of my favourite combinations to achieve the tones I love.

First of all, I have something to say about black. I’ve learned from experience that black can easily dominate a watercolour picture. Look around you: most of the things you think on first impressions are black are not actually true black - most likely they are a kind of dark grey, or a warm kind of black or a cool kind of black… do you see what I mean? For this reason, I almost never use actual black in my paintings (other than in the ink outlines). Instead, I either water it down heavily until it becomes a kind of grey, or I use this blend in the top row…

TOP ROW: The “sort-of black” here is achieved by blending dark blue and dark brown together. If I want a warmer black I add more brown, if I want it cooler I add more blue. Because it’s not “true black,” it looks more natural on the page.

SECOND ROW: I mix light-brown, orange and white together with a fair bit of water to create this kind of neutral sand, which forms the base for all kinds of other colours I need. It goes well with greens, and is also a good starting point for skin-tones, as it can go lighter, darker, or a touch pinker

THIRD ROW: I paint a lot of botanicals, but find the ready-made greens are often unnatural. Also, there are just so many shades of green in nature, just one or two won’t cut it. Depending on what I have to hand, I most often mix a lighter green with a darker green, and then play with adding either light brown, yellow, or the sand I created in the second row above, to get the right tone for the leaf I’m painting.

FOURTH ROW: I’m not a fan of “candy pink” but I love a duskier pink in everything from flowers to sunsets to balls of knitting and an old lady’s hat. I get this by blending the dark red in my paint set with a kind of fire-engine red/orange also in the set, and then adding white until I get the exact depth I want.

BOTTOM ROW: The dove blue/grey here is one of my favourite colours, and I get it by mixing royal blue (as opposed to the dark blue of the top row) with dark brown, and white. It is a much prettier and more natural sky than just watered-down blue, and by adding a tiny bit more brown I can turn it into a lovely, soft grey, that is nice for animal fur, for example, or to add shading and texture to the bark of trees.

(NOT PICTURED BUT HANDY): Purple is quite difficult to make. Most of us know to blend blue with red, but too much red and you quickly get brown instead. I try going lighter first: I’d probably blend the dusky-pink and dove-blue colours in the bottom two rows together, to create a soft kind of lilac, then I’d add more of any of the colours in those two rows bit by bit, in order to get the exact tone I wanted. For me, this is easier than starting from scratch with just red and blue.

4. How to shade a painting

One of the easiest ways to bring a painting to life is to add shading. This not only makes whatever you’re painting look more three dimensional, it also adds interest and texture to what you have created. Imagine a painting of a cactus in a terra-cotta pot. You could simply paint the pot a terra-cotta kind of orange, OR you could create shading to help it look round, rough-to-touch, and give it that lovely aged patina that real terra-cotta gets.

Here are some of my tips and hacks for shading a painting:

A consistent light-source

The most important thing is to imagine a consistent light-source. Imagine shining a spotlight on whatever it is you are painting, or imagine which way the sun is shining or where the window is. Keep that light-source consistent in your entire pattern. It will do all kinds of weird things to people’s brains if the shadows on one part of your picture are on the left, and in the other part they are on the right. Light doesn’t do that (unless you’re a surrealist painter).

It’s lighter where the light is (duh, Naomi)

If the light is coming from the right, everything on the right-hand side of your picture (from terra-cotta pots to trees to animals to a bottle of wine) will be lighter and brighter on the right, and darker on the left. If the light is shining straight in front of your thing (like your terra-cotta pot), then it will be lighter and brighter in the middle, and get darker on either side. If the light is coming from directly above, the leaves at the top of your plant will probably be lighter than those at the bottom.

Shadows are not only about light and dark

Shadows don’t have to be created by simply applying lighter and darker versions of the same colour. Here are some of the ways that I create shadows in order suggest a light-source and create interest:

a) By using more or less intensity of the same colour (by adding more water to make it less intense)

b) By putting a watery drop of dark-blue, black or dark-grey into the areas that I want to shadow, after applying the first ‘main’ colour

c) By blending up two versions of a colour, one that is darker and/or more intense for the areas that are to be in shadow (for example in the case of a terra-cotta pot, I will often blend up two versions of the neutral ‘sand’ colour I shared above, one that has slightly more light brown in it, and another with a bit more pink. The first will be my main ‘in the light’ colour, and the second will be the darker shadows)

d) By using a completely different colour for the shadows, which might be unexpected but, because it is darker or stronger than the lighter areas, still tells viewers’ brains: “this is shadow.”

e) By painting the object one colour, and then “blotting away” the part I imagine to be in the sun, by pressing a paper-towel down over that part. Pressing the paper towel down immediately will remove all the colour. Instead, I like to wait a short while (a minute or thereabouts) and then press - that will take away some of the intense colour, but leave a softer version.

What ever technique you use to create shadows, if you want to have a soft or even invisible transition between the light and shade sections, a good tip is to take a clean, wet paintbrush and gently brush water over those “transition lines.” I don’t always bother with this because sometimes I like things to look a bit more rough and deliberate, but you can create a very natural, organic transition from light to shade if you want to, just using water in this way.

Here are some examples of different ways I’ve created shadows:

In this partial painting of a castle in Dinan, I used a watery dark blue to create the shadows, despite there not actually being any “blue shadows” on the golden stone walls

In this painting of a whale I made for a Boots Paper greeting card, I used a rather unnatural aqua blue as the shading at the bottom of his belly. The brightness of the blue, and contrast to the much more washed out almost-white of his body, creates the shade I wanted, while also suggesting a watery “whale in ocean” feel that I wanted, despite not painting the ocean

In this greenhouse mail-art picture, I used three different blends on the terra cotta pots to show the light, middle and dark sections of the pots (and to add interest and texture), and blotted some of the way almost entirely, then added white paint, in the areas I wanted to appear super-light. (Here is another picture of pots in which I was - slightly - more subtle in the shading)

5. Paper, and paper towels

Paper weight

(As in, the weight of the paper, not the old-fashioned paperweight that your grandfather kept on his desk).

In general, it is best to paint with watercolours and gouache on paper that has been specially made for that purpose. Watercolour paint is thicker than ordinary paper, which helps to stop it from going bumpy and buckling with all that water. So to give you an idea:

Ordinary copy-paper is usually 80gsm (gsm just stands for “grams per square metre” and refers to the weight, or thickness, of the paper)

A fairly average watercolour paper thickness is 185gsm

Obviously, you can experiment to see what works for you. I have used copy paper plenty of times in my mail-art, and just flatten it down under books overnight if it buckles too much.

But if you pop into an art supplies store and ask to buy watercolour paper, it can be a little overwhelming. There’s weight, there’s texture, and there’s all those different methods of making the paper itself. How do you choose?

Here’s what I have experienced so far (although please remember - see the top of this longgggg blog post - that I am an amateur):

Rough, textured watercolour paper looks fantastic on those old watercolour landscape paintings you might have seen. It gives a lovely tactile feel to the painting

If you want to paint something for printing (such as something for a book or stationery, like my illustrations for Boots Paper), the texture might go against you, because it will stand out too much against the smoothness of the page elsewhere

Paper that is “hot pressed” gives you that smooth feel I’m talking about, and the other benefit is that the paint dries quite quickly on it so you can layer your colours on quickly

Paper that is “cold pressed” tends to be slightly more textured (though not necessarily as rough as the old-fashioned paper I mentioned earlier) so the paint stays wet longer if you want to create some effects using water and blends. (As an example of this, take a look at the image of food around a grey dinner plate I shared earlier: the dinner plate was left blank because a logo was going to be added inside it, but for subtle interest, I used a lot of water to create that slightly ‘bleeding’ effect you see, reminiscent of glazed pottery)

Most watercolour paper is either cream or white - think about what you mostly like to paint when you choose, and the tones you prefer. For my Boots Paper illustrations I use a slightly more creamy background, because that is what Boots’ owner, Brenner, prefers. For my own work I like a brighter white, because I prefer cooler tones

Preparing the paper

Confession: I never do this. I mean never. I have never even tried it. However… best practise is probably to stretch and then tape down watercolour paper, to ensure you have a perfectly flat surface, and that the paper doesn’t buckle with all the water you apply.

Perhaps if I painted more landscape-style images with big wash areas, I’d have felt the need to learn how to prepare my paper sooner, and have cultivated this good habit. Because my illustrations are mostly quite small, it hasn’t been an issue (so far).

If you want to learn how to prepare your paper (or want to teach me), here’s a tutorial.

Paper towels

My favourite painting tool, other than paints, brushes and water, is a trusty paper towel. My favourites are the kinds that have little patterns embossed on them. I always have one or two paper towels beside me when I paint, and I use them to:

Clean brushes (after I’ve cleaned them in water, I wipe them off on paper towels to be sure they don’t have any paint residue left on them)

Blot away mistakes (if the paint is still wet, you can blot it with a paper towel and you are magically back to blank paper! Even if the paint has partly dried, try wetting it thoroughly with a brush, then blotting)

Blot sections of an image to create a feeling of light and shade, as I mentioned above

Create texture. If there are embossed patterns on the paper towel, it can be fun to actually use this in my painting: I press the paper towel over the paint while it is not quite dry (but not super wet or the paint will disappear) to create a fun, mottled pattern

Here is a short video in which I use a paper towel to create light and shade in my picture, let the paint partially dry (while I sip tea, naturally), then create a new layer in a different colour.

I hope this blog post was useful! I feel a little bit silly and vulnerable writing about “how to” on something I really do just muddle through, and feel about as far from being an expert as you can possibly imagine.

This lack of training probably makes me a fairly poor instructor: if there was something you were wanting to know from me about how I do my painting, but I’ve failed to mention it here, feel free to ask away. Likewise, if this actually is useful to you and you’d like to know more (such as some tips on drawing, for example, which in all honesty would be equally bumbled-through), let me know and I’ll see what I can come up with.

But no matter what, I DO hope this long post inspires you to pick up that dusty old paint-set (yes, the one you picked up for your kids at the supermarket) and wile away an afternoon playing with colour.

Dreams come true

This is one of the most exciting announcements I've been able to make in a very long time.

This is one of the most exciting announcements I've been able to make in a very long time.

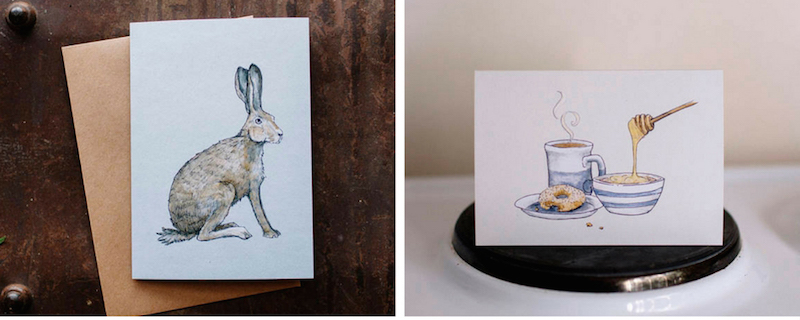

Earlier this year, I received an email from the owner of my favourite paper company, Boots Paper (I wrote about them here), inviting me to design my own stationery! I sat there at my computer, reading that little message from one of the most beautiful, high-quality, ethically-produced stationery companies going around, inviting me to put my own stamp on their products, and had to pinch myself.

I decided to play it cool and act like this was the kind of invitation I received every day, as opposed to what it actually was: a dream come true. Moments later I utterly lost my cool and immediately hit reply with a resounding YES. I think I might even have written "This is a dream come true."

The original brief was to create two different notebook designs, the type that I would love to use myself if I was to sit and write a lively, personal letter (or write a lively, personal shopping list, for that matter). I got straight to work, and sent in those paintings, and then we started on some more. Swing tags, stickers, greeting cards, postcards, envelopes and more; featuring animals, botanicals, people, retro hobbies, food and hygge. And so much more.

And today I am proud (SO PROUD) to announce that the very first of my designs are now available for sale on the Boots Paper online shop, as well as in Boots stockists all over the country.

They are the greeting cards you see in this blog post: hand-drawn and then painted by me in watercolour, gouache and ink; printed on 100 percent recycled paper; with matching envelopes that have been printed on the inside; all hand-assembled in Gippsland, Victoria.

Eeep!

There's more to come, so please excuse me while I go and paint some more. xo

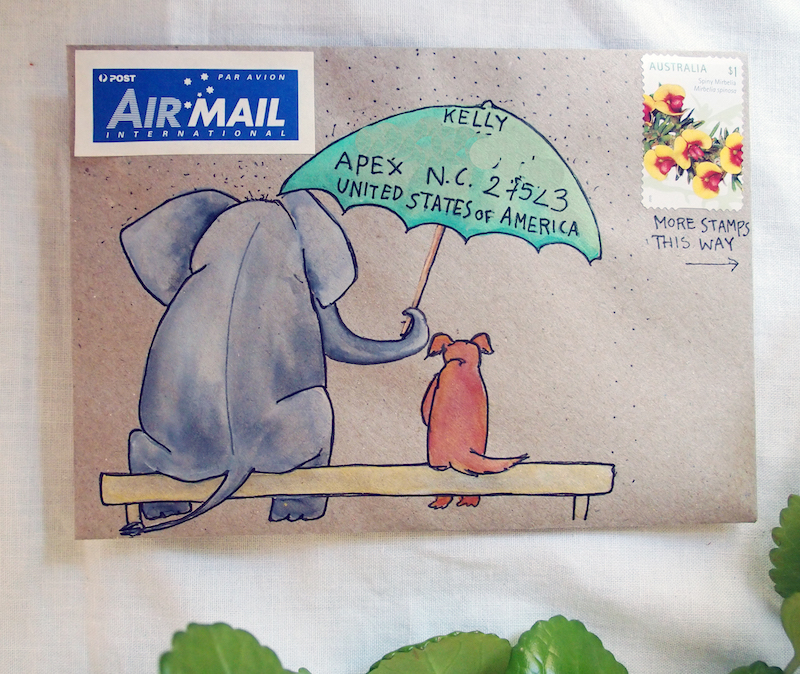

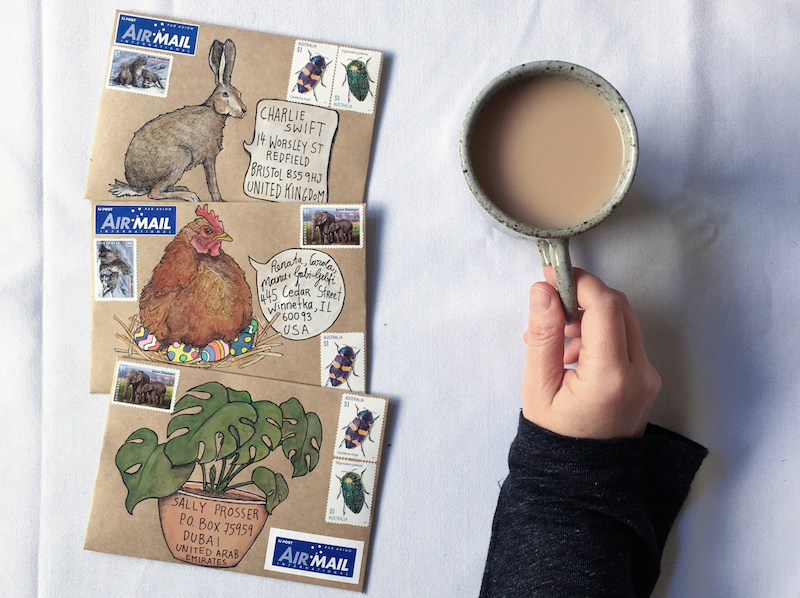

ps. If you like these or any of the other Boots Paper designs, they ship anywhere in the world, and everything is hand-packaged beautifully. Just take a look at this package sent to me on a recent order! Leave a little note for the lovely owner, Brenner, to tell her I said hi.

Celebrating the makers

Above: a collection of envelopes using my designs by @sculptedfilms on Instagram

Above: a collection of envelopes using my designs by @sculptedfilms on Instagram

Can we all please just take a moment to appreciate all the lovely work that people all over the world are putting into these print-and-paint snail-mail templates?

I have put off writing this blog post because I didn't know quite how to express how happy it makes me, sending my mail designs into the world, and then seeing how people are using them and making them their own, in order to send creative mail to others. It still sounds trite when I put it like that, but it truly warms my heart to see people actually using and enjoying what I make... and knowing that they in turn are bringing joy to others through the post.

Above: transparent envelope by Snailmailcool on Facebook

Above (clockwise from top-left): coloured envelopes by @murderingtime on Instagram, @lyndsey.thiessen on Instagram, @seniahhandmade on Instagram, @allyt_hobart on Instagram

Above left, rainbow hare envelopes by @lyndsey.thiessen on Instagram, top right by @elisef03 on Instagram, bottom right by @allyt_hobart on Instagram

Above: strawberry, flower and book envelopes by @murderingtime on Instagram

If you don't know what this is all about, I create envelope templates with mail-art designs on them, that people can print off and turn into decorative envelopes to send through the post. They are free, and I send new designs out every month via my newsletter, Snail Mail Toolkit. You can sign up to receive them (as well as a free copy of my e-book, Making Mail: 10 steps to writing letters that become keepsakes, here.

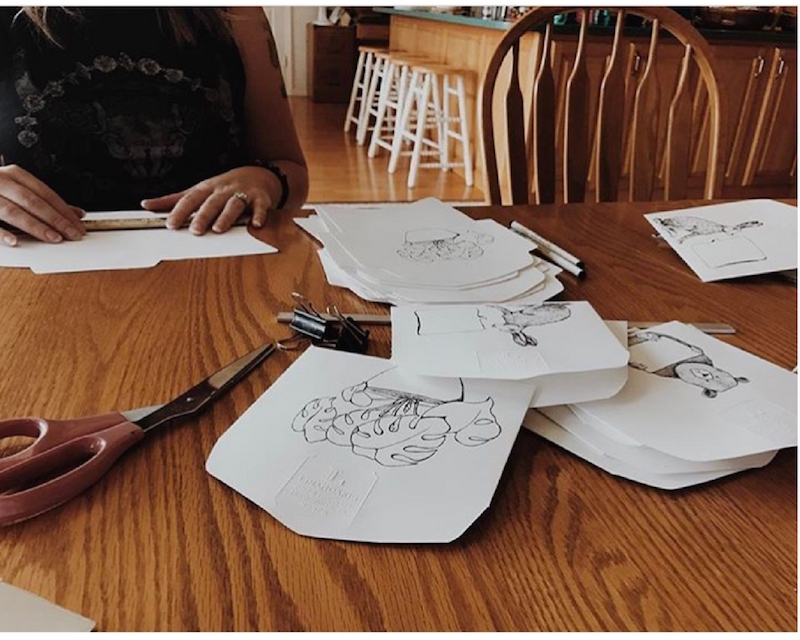

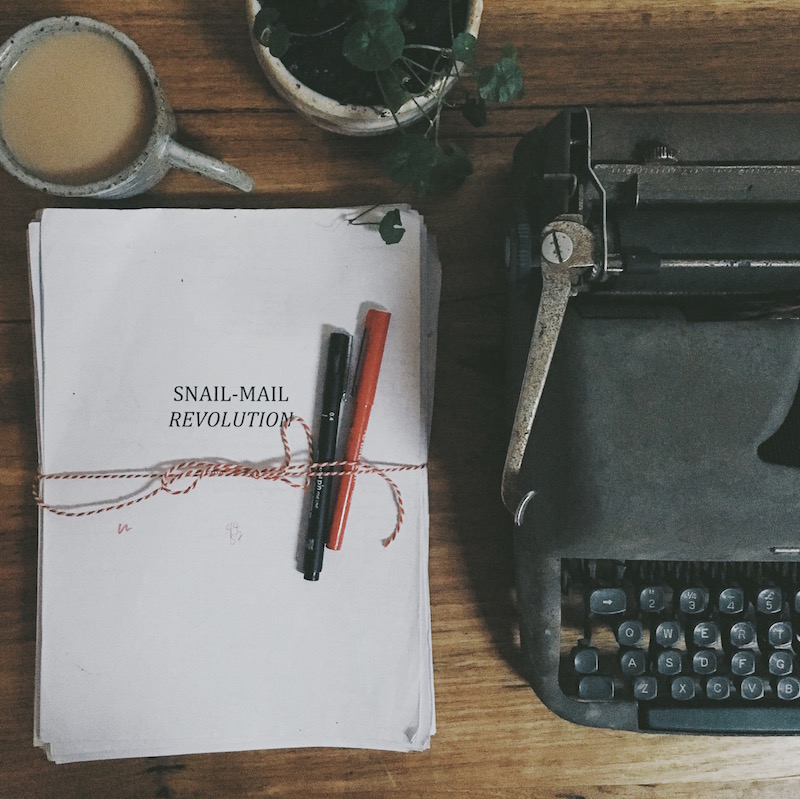

Sneak peek inside the April Snail Mail Toolkit

This is a sneak peek at the mail-art templates I'll be sending out in my Snail Mail Toolkit newsletter on Saturday morning. Would you like to make this mail? It's a gift from me to you!

This is a sneak peek at the mail-art templates I'll be sending out in my Snail Mail Toolkit newsletter on Saturday morning. Would you like to make this mail? It's a gift from me to you!

I'm on a mission to bring back old-fashioned hand-written correspondence. Why? Answer these questions in your head:

- When was the last time you received an email? How did it make you feel?

- When was the last time you received a hand-written letter in the mail? How did that make you feel?

The practice of writing a letter is nostalgia, crafts, slow-living and community all rolled into one. And that's just for the sender. Imagine how it makes the recipient feel!

I launched my newsletter at the start of this year because I wanted to make it as easy and inspiring as possible for you to send somebody a letter... and to make it special with mail-art.

Every month there are templates with designs like the three above. All you have to do is print them out, follow the fold-lines to create the envelope, and add in the address. If you want to get more creative and have the time, you can do more, painting the designs as I have done, or colouring them, collaging over them, creating a washi-tape border around them, or any other crafty idea you have.

I also include ideas for what to write, or who to write to, or what else to include in your mail. And to help you get started, I send a copy of my e-book, "Making Mail: 10 steps to writing letters that become keepsakes," to newsletter subscribers, with some more detailed guidance to making mail.

If you like the look of the envelopes above, I'd love to see you make them too! I send new designs every month and once you download the templates, you can print them off as many times as you like (I used a slightly heavier recycled paper here, but normal copy-paper works fine). It's like having a never-ending stationery supply at your fingertips!

This blog post sounds like an ad doesn't it, but I promise it's all free (no strings!), so how I'd really like it to read is as an opportunity. Or an invitation. I just really want to see you feeling encouraged, inspired and empowered to write a letter to someone and to have a bit of creative fun with it.

You can subscribe to the Snail Mail Toolkit right here. Be sure to subscribe before 9am Saturday Melbourne time (heads up northern hemisphere readers that's your Friday) for these designs.

Finally (oh hi! thanks for still reading!) if you could help me spread the word about the Snail Mail Toolkit newsletter by sharing this post on your social media, that would be SO WONDERFUL of you. Maybe together we can make snail-mail mainstream again. (I think they call that the #snailmailrevolution)

ps. If you're on Instagram, pop on over to visit me later this morning, because I will be launching a lovely little giveaway to win some beautiful Boots Paper stationery (remember the post I wrote about Boots Paper last year?). You can find me on Instagram here.

The honeybees and me

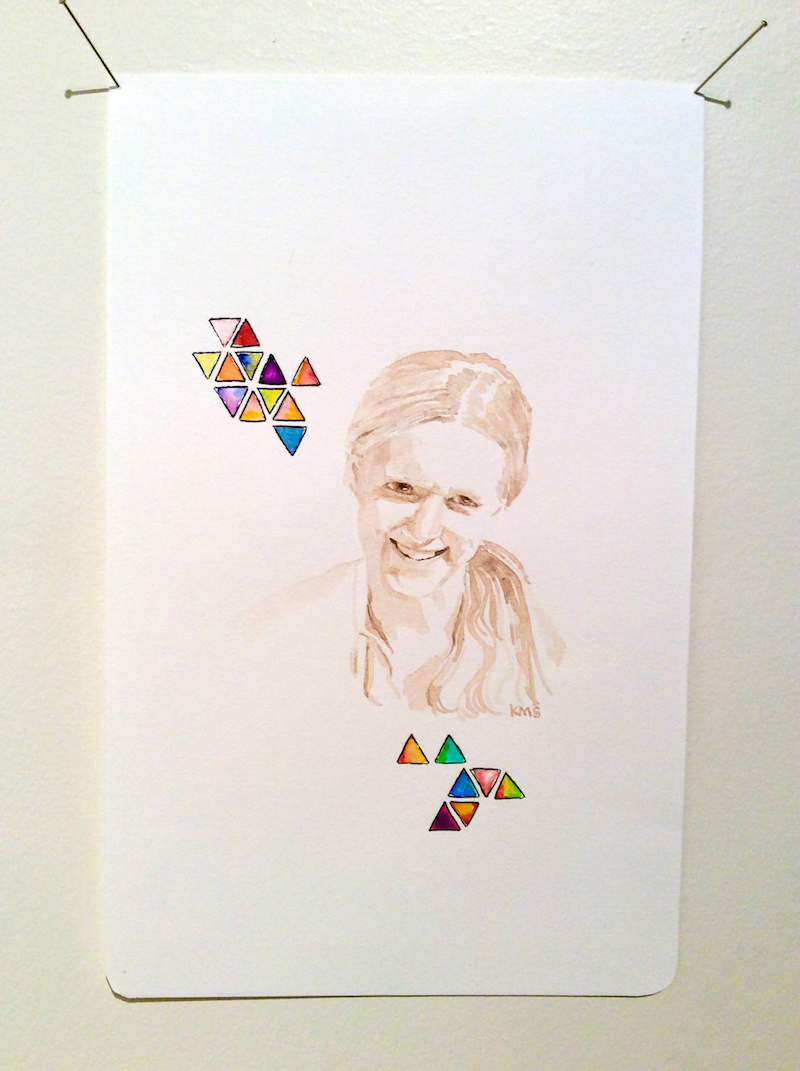

Oh hello. Look, that's me in the picture!

Recently I was approached by New Zealand artist Katherine Steeds to have my portrait painted. (I know - lucky me!) It was to be one of 50 small, sepia watercolour portraits (each about the size of a postcard) which, when exhibited together, would cluster and flutter on the gallery walls a lot like a friendly swarm of honeybees.

The exhibition was to be called "The Bee Appreciation Society AGM," and Katherine's purpose was to draw attention to the plight of the honeybee, globally.

You've probably heard the disturbing news that our pesticides are killing our bees. The National Geographic says world is in an unprecedented "pollinator crisis," and projections are that this year we will lose close to 60 percent of the world's honeybee population.

This is sad in its own right, because, the poor bees! But there are some fairly serious implications for us, too, and they are a lot worse than missing out on delicious honey for our toast.

A full third of our foods rely on bees for pollination, including apples, nuts, pretty much all the summer fruits (like stone fruits and berries), onions, broccoli, alfalfa (which is eaten by cows), and a whole lot more.

I don't know about you, but I'm not ready to give up all those delicious foods (up to 100 crops are being impacted) just yet!

Plus, bee health can tell us a lot about environmental health, and therefore about our own wellbeing.

Here are some actions we can all take to help save the bees:

1. If you have room for growing things at your place, plant bee-friendly flowers and flowering herbs in your garden or pots 2. Don't use chemicals and pesticides to treat your garden or grass (products like “Round Up” weed killer and “Confidor” insecticides have been proven to harm bees. Glyphosate – the active ingredient in Round Up – has been banned in several countries for being carcinogenic) 3. Where possible, try to buy organic, pesticide-free, GM-free produce (organic farmers' markets are a great place to find good produce, often a lot cheaper than organic food in the shops) 4. Buy local, raw honey (this is honey that hasn't been treated with chemicals or processed with heat to stop it crystallising.) An added bonus is that it carries a lot of health benefits: it's a good source of antioxidants, has antibacterial and antifungal properties, is filled with phytonutrients, and tastes delicious!

There is some more useful information about this issue on Save the Bees Australia if you want to read up on all this.

In the meantime, pop on over to Katherine's Facebook page and start a conversation with her!

Mail-art: picturing kindness

With everything going on in the world towards the end of last year, I got to thinking about kindness, and what it meant. Why did some people seem to have it in spades, while others could act with such coldness, such brutality, that surely all compassion, all empathy, must have been clinically removed from their souls? I find cruelty - not angry passion but callous cruelty - truly incomprehensible.

In all this thinking, I started to wonder what "kindness" meant to people. Because I'm fairly sure that, aside from genuine psychopaths, the people who I believed were speaking or doing things of utmost horror probably believed that they were actually good people, at least some of the time. They are not all villains, retreating to their lairs and laughing "BWAHAHA" every time they commit an atrocity. Somewhere along the line, these human beings have either justified their actions due to their beliefs, or have become immune to the suffering of others, because the mind is frighteningly good at self preservation (and nobody wants to admit to themselves "I am evil.").

I refuse to believe that that people are black to the core. Small-minded, intolerant, cruel, yes. But maybe not evil through and through? I don't know. I hope not. If you think terrible things cannot be done within the pretext of noble intentions, just ask any religious extremist, ever.

Where is the kindness in all this? How can a man murder in the morning and let the dog sleep on his lap in the evening? Torture someone one day, and buy his mother fudge the next? Show hatred to an entire race of human beings, but love his children?

Mail-art isn't going to solve any global or existential problems just yet, but this was all at the front of my mind as I was painting these envelopes, so I decided to follow it through. I did a Google image-search on the word "kindness" to see what other people saw in their minds when they heard that word. These envelopes are my interpretations of some of the images at the top of that search.

What does kindness look like to you? What would you draw, if you got "kindness" in a game of Pictionary?

ps. have you heard about my new letter-writing and mail-art e-course?

Over four weeks, I will guide you through multiple methods of making beautiful mail-art and creative, handmade stationery; teach you the art of writing and storytelling; help you forge personal connections in your letters and find pen-pals if you want them; and share time-management tips so even the busiest people can enjoy sending and receiving letters. Register your place or find out more information right here.

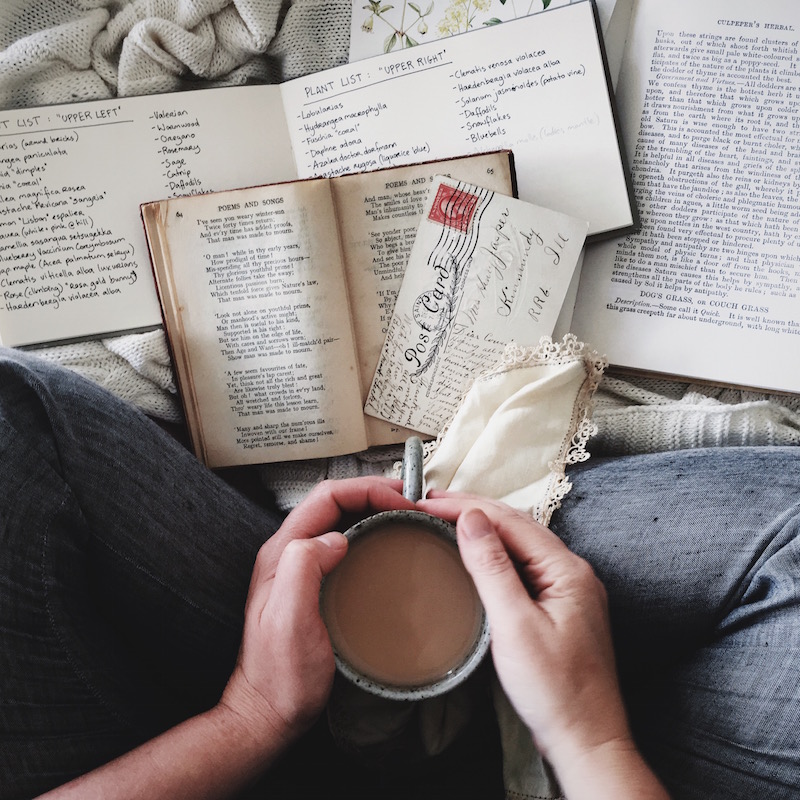

Just what you needed to hear

I've been doing a course on Instagram, trying to improve my photography and Instagram engagement in general. It's challenging, fun, inspiring, and frustrating, like most things are when you're learning something new. Then today, someone else in the course shared this video with the class.

I'd heard of this little piece by Ira Glass before, but had never actually taken it in myself. If you're struggling with trying to be creative - or really, with trying to be good at anything in life - and you feel like you're just not up to scratch, do yourself a favour and spend two minutes listening to this. (If you can't see the video below, click this link to find it in Vimeo).

It just might be exactly what you needed to hear.

THE GAP by Ira Glass from Daniel Sax on Vimeo.

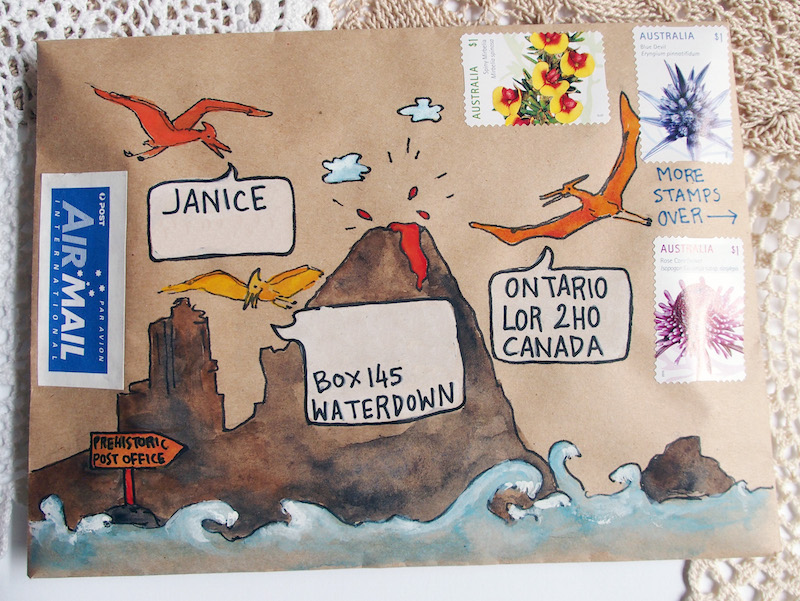

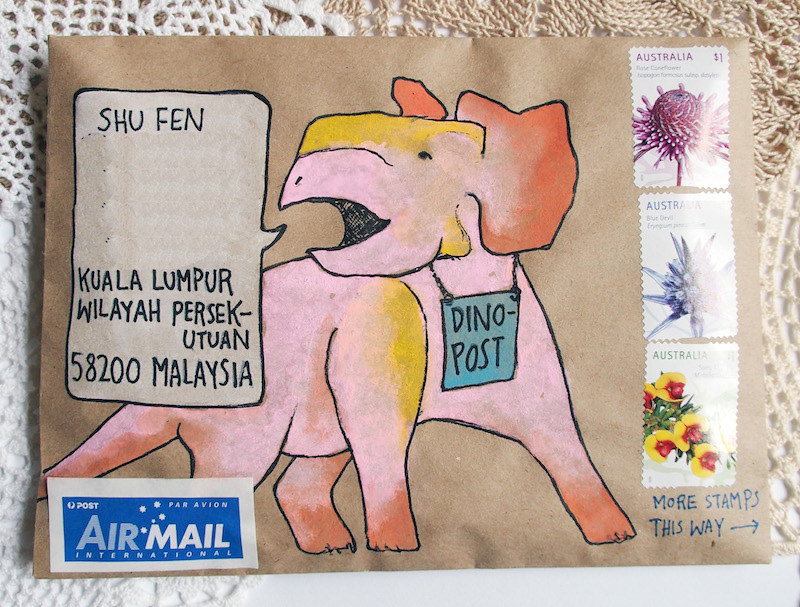

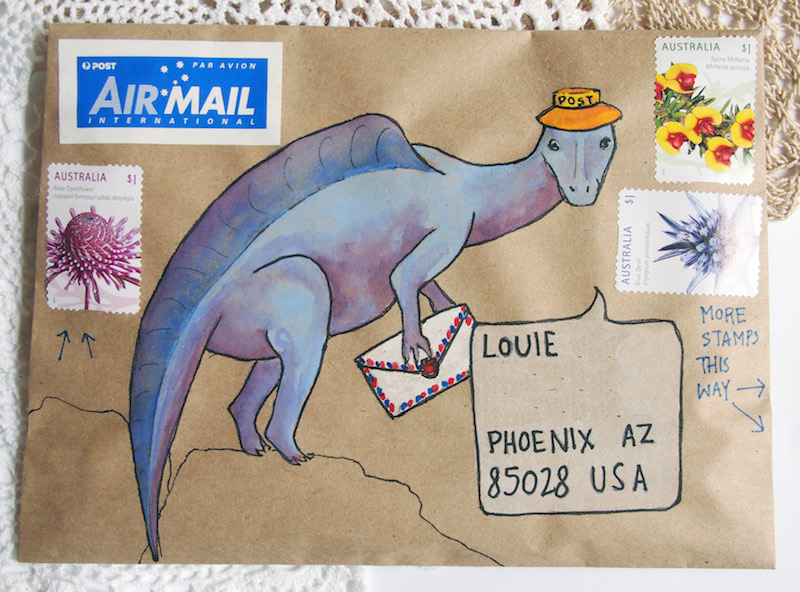

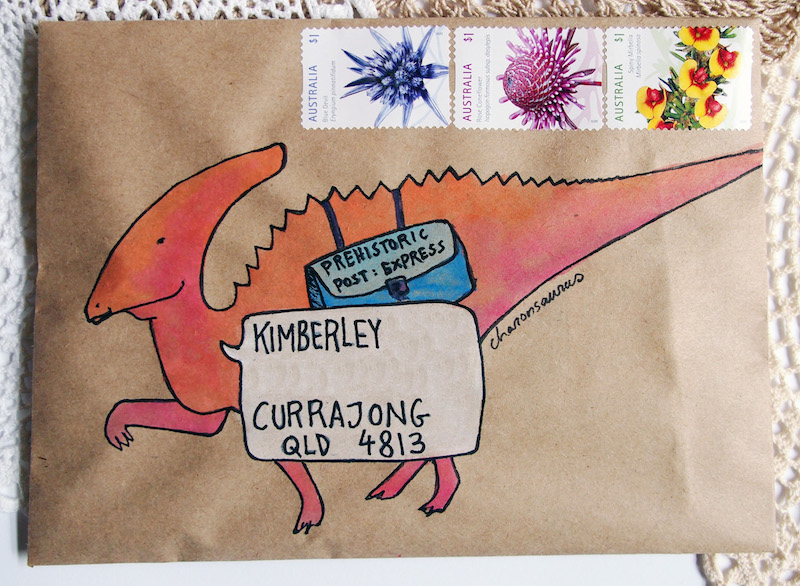

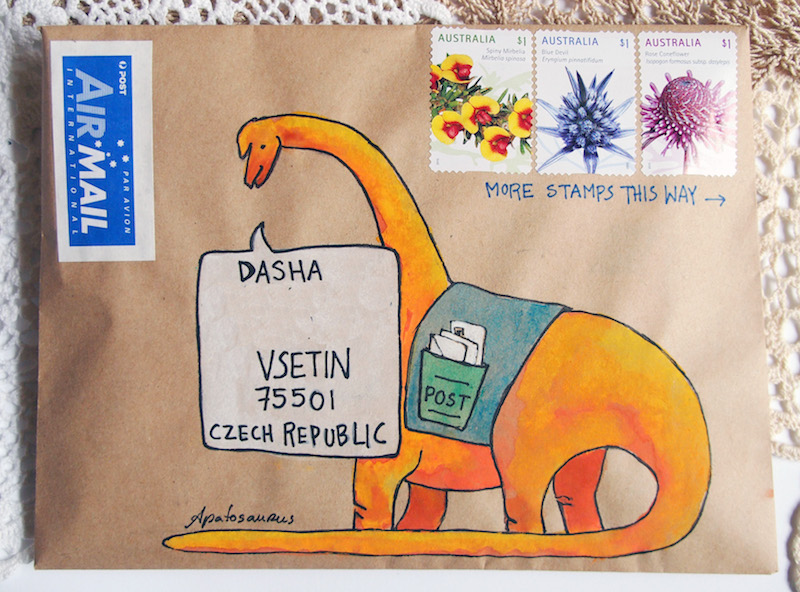

Mail art - prehistoric post

We cut our way through a tangle of vines, each one thicker than a man's arm. Heat prickled our skin. The air was humid, tropical, and thick with floral perfume: something like frangipani, with a less-pleasant undertone of... what was that? Sulphur?

We cut our way through a tangle of vines, each one thicker than a man's arm. Heat prickled our skin. The air was humid, tropical, and thick with floral perfume: something like frangipani, with a less-pleasant undertone of... what was that? Sulphur?

When at last we pushed aside the final curtain of vines, we could barely believe the evidence of our eyes. A volcano, forcing its way up out of the ocean, and, around it, a flock of pterodactyls carrying mail bags.

We had discovered it at last: the lost island of the Prehistoric Post Offie.

A recipe for mail-art

I have been so busy making mail lately! Cutting out little packets of handmade stickers and labels, collecting vintage stamps, hunting for postcards old and new, photocopying old recipes and household tips that once belonged to my great-grandmother, then bundling them all up together in handmade envelopes from old catalogue pages, melting green or red wax over the fold, and sealing them shut with a big, bold N.

Lately I've noticed that a lot of you guys have been using the comments section of this blog to ask for tips and tutorials on how to create mail-art. So I'll do my best to oblige you in this post but, to be honest, the beauty of mail-art is that there are no rules and no standards. No tests to pass, no clubs to join, nobody to judge the "artistry" or talent of your work. Or mine. If you put some creative effort into it, and if you call it mail-art, it is mail-art.

That being said, here's the process of how I personally choose to whip up a batch of mail-art (and if you're new to this blog, samples of the finished products are here).

Ingredients:

* Brown kraft paper * Scissors * Glue-stick * Pencil (I use 2b) * Eraser * Pencil-sharpener * Black felt-tip pen (waterproof) * Watercolour paints * Gouache paints * A variety of watercolour paint-brushes * Postage stamps * "Via Airmail" stickers (if applicable) * Sticky-tape * Washi-tape (optional) * Sealing wax and seal (optional)

Method:

Step 1: Most of the time I hand-make my envelopes out of brown kraft paper. To do this, I open up an existing envelope and use it as a template, to trace onto the kraft paper. Cut it out, and glue the sides together. Use a glue-stick or paste rather than liquid glue, so you don't end up with lumps and bumps in your envelope.

TIP: I like to make the envelopes so that the rough side is facing outwards, rather than the shiny side, because it takes paint better later on when you come to that

Step 2: I roughly draw my design onto the front of the envelope, in pencil. This means sketching a drawing - a plant, an animal, a cup of tea, and working the address into the design. Sometimes I write the recipient's name and address next to the drawing, but if possible, I try to fit it into the actual drawing, such as onto the petals or leaves of a flower, a mug of coffee, a speech bubble, the pots of a series of house-plants.

TIP: In your design, leave enough room on the top right of the envelope to fit one or more stamps later on

Step 3: Now I go over my drawing with a firmer hand, using a black, felt-tipped pen. I use the Sakura Micron brand, and have a pack of pens that range from point 0.1 to 0.8 in thickness, depending on what kind of line I hope to create.

TIP: Always use water-resistant ink. This way when you paint them the ink won't run, nor will the essential details (addresses, for example!) run if the letter gets wet in the rain

Step 4: Next, I paint my design using a mixture of watercolours (Winsor & Newton) and gouache (Reeves). Gouache creates a thicker, chalkier, brighter colour than watercolour, especially on the brown paper, so I use these paints where I need the colour to stand out. I use watercolours when I want more subtlety. To help the postie read the address in my mail-art, I aim to make the parts of the picture containing addresses brighter and lighter in colour than the others.

TIP: When sending mail overseas, it's important that the destination country is big and clear and, if possible, in the same area or colour as the rest of the address, so it won't be missed

Step 5: Once the paint is dry, I pull my felt-tip pens back out, and go over the outlines again to give the drawing definition. This is particularly important to ensure the address is clear and stands out, even more-so if I've used gouache, because if applied thickly it can be quite opaque, and the writing needs to be reinforced over the top.

TIP: If I feel the postie may need more direction to send this mail where it is supposed to go, I draw little arrows pointing to the start of the address, and write the words "Kindly deliver to" above the recipient's name

Step 6: Now I put the stamps on the front-right. Rather than use those ugly Australia Post printed labels, I prefer to use lots of stamps to make up the postage. If they won't fit on the front without ruining my design, I continue them over onto the back of the envelope.

TIP: If you need to do this, too, make sure that there is at least one stamp where it is supposed to be, and write the words "More stamps over" to ensure your postie knows to look there

Step 7: If I'm sending my letters overseas, I affix a "Via Airmail" sticker to the envelope. It's supposed to go on the top left-hand side, but fitting it anywhere is usually enough to alert the postie to the fact that this is international mail.

TIP: If your mail is travelling domestically, don't stick a "Via Airmail" sticker on it. I've made that mistake before, and the postie has confused my letter for international mail and not known where to deliver it

Step 8: Almost done! Next, I clearly print my return address on the back of the envelope. I had a stamp custom made to do this and I don't know why, but it gives me a lot of primitive pleasure to ink it and stamp it onto each letter.

TIP: If you've needed to add extra stamps to the back of your envelope as per Step 6, make sure you write the words "Please return to" or "From" above your return-address, so the postie doesn't mistake it for the destination address, surrounded as it is by all those stamps

Step 9: Finally, I fill the envelope with all the contents I have created and collected, then close up the envelope with sticky-tape. This doesn't look very good so, if possible, I then cover the tape with something pretty, like wash-tape, a handmade sticker label, or another wax seal.

TIP: Make sure there are no loose parts of your envelope that could catch on things and tear during its long journey through the post. Tape everything down

And that's it, my process for making mail-art from start to finish.

How about you? How do you like to decorate your letters? What ever you do, please know this one thing: if you get creative with your mail, you are a mail-artist.

ps. If you're in the mood for even more letter-writing inspiration, I want to remind you about my letter-writing and mail-art e-course, "The Most Beautiful Letter You Have Ever Written."

Over four weeks, I will guide you through multiple methods of making beautiful mail-art and creative, handmade stationery; teach you the art of writing and storytelling; help you forge personal connections in your letters and find pen-pals if you want them; and share time-management tips so even the busiest people can enjoy sending and receiving letters. There's also a host of downloadable resources, and access to my own private mail-art pen-pal group. Registrations are open right now, and you can find out more here.